As I mentioned in two (long) posts on how comprehensive measures of household consumption or disposable income explain high US national health expenditures (NHE) rather well, I believe US health expenditures are overwhelming accounted for by higher volume of health consumption (the quantities of goods and services consumed in the health care sector). I reject the popular notion that idiosyncratically high prices are what causes the US to spend so much more than other OECD countries and I reject the notion that rising health prices explain why US health expenditures have grown so much faster than income over the past few decades (at least).

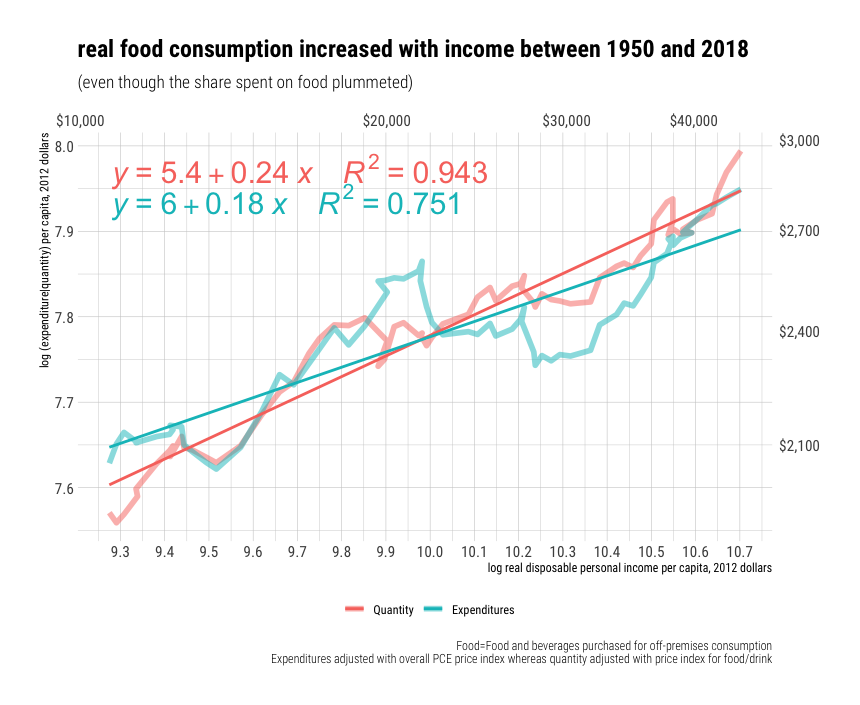

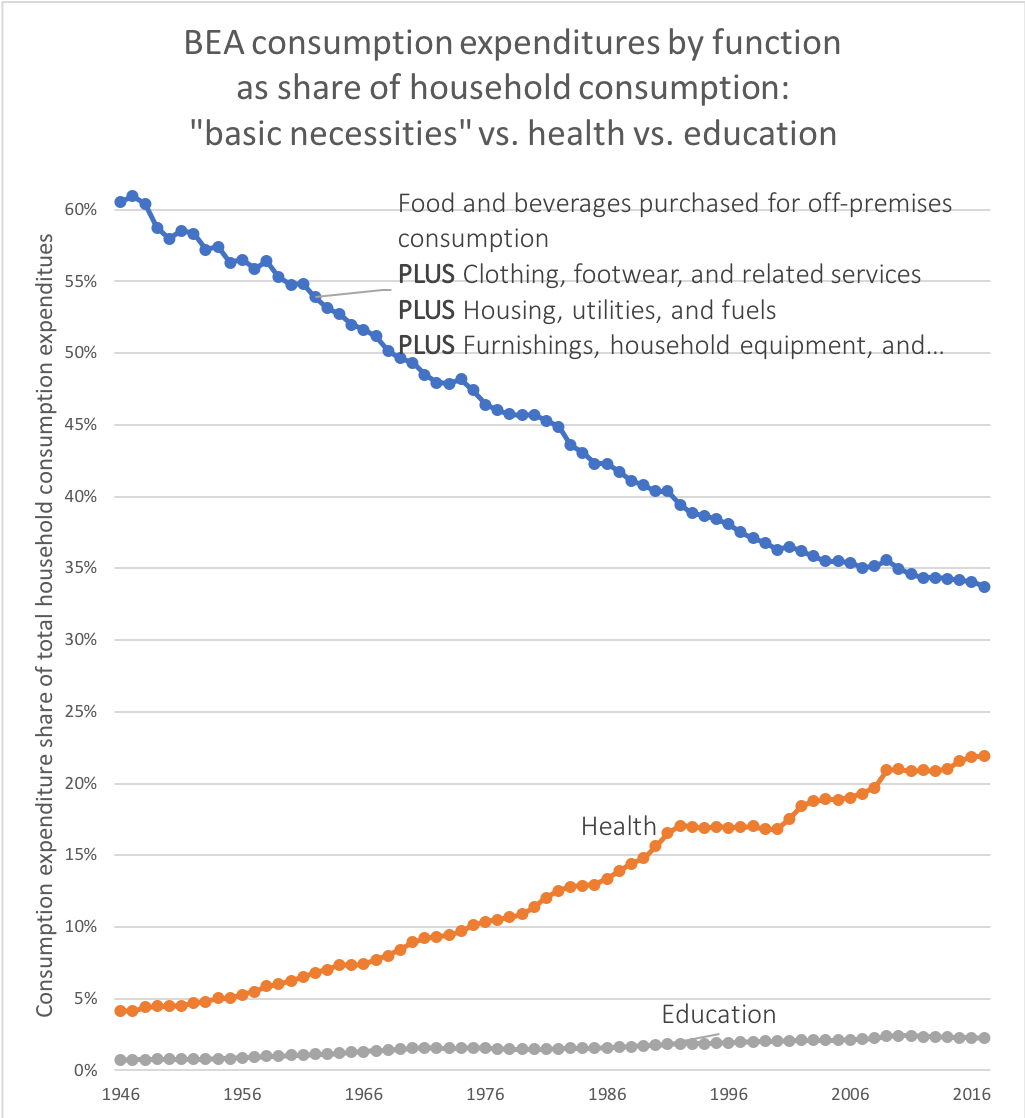

This does not mean that prices play no role whatsoever in international comparisons of NHE. It does not mean, for instance, that if we could somehow force U.S. physicians, nurses, and various other workers in the health care sector to work for the real remuneration paid to their counterparts in, say, Brazil with equal productivity that the price of medical care, especially more labor intensive categories, would not plummet (presumably real NHE could decrease if volume were hold constant…. not a very safe assumption imo). It means that the reason health expenditures have accounted for an increasing share of our consumption (or income) over time has little to do with prices increasing relative to income and a great deal to do with the volume of health goods & services consumed rising at a faster rate than overall consumption (or income) per capita.

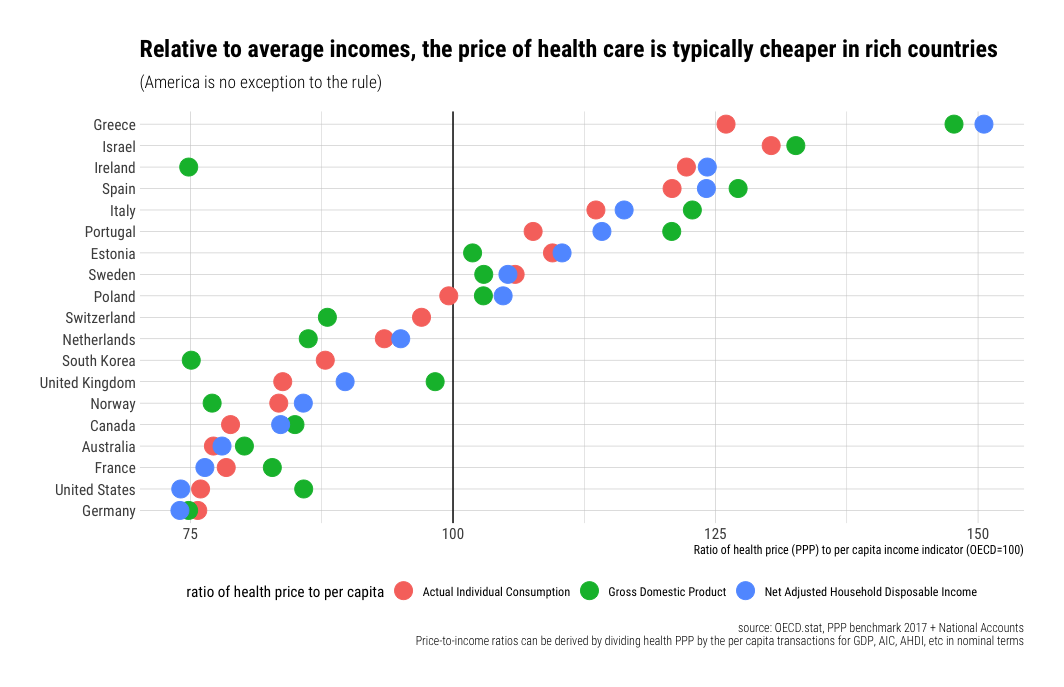

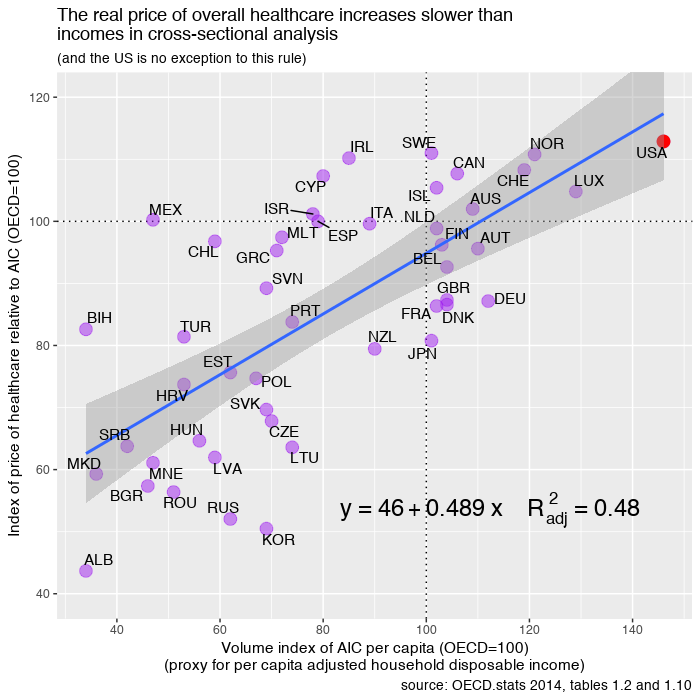

Much the same goes for international price comparisons in cross-sectional analysis. The cost of an internationally equivalent basket of health care (both goods and services) rises a little faster than the cost of a broader, economy-wide/GDP, basket of goods and services with rising income levels, but it does not rise all that much faster with respect to income (actually somewhat less overall in the long run).

In order to significantly explain the presumably large US residual in NHE per capita (obviously I don’t quite agree with this perspective) there must be a large residual in the actual relative price levels; we simply do not find any evidence of this with the best available evidence. With better data US residual is either slightly above trend (by no means an “outlier”) or below trend, depending on the precise predictor (e.g., GDP, AIC, average wages, etc) and the basket of goods and services employed. In no case do I find evidence of a large departure from trend in any broad, highly impactful, index of health price levels that would suggest that high US NHE isn’t overwhelmingly explained by high volumes of (real) health care consumption. More generally, the cross-sectional and time series data are actually quite consistent with each other, i.e., the issues that drive (US) expenditures up in time series are quite consistent with and related to the what we observe in cross sectional analysis between countries.

Continue reading