Disclaimer: The title of this post is somewhat tongue-in-cheek and I fell slightly short of one million charts. Also, Noah probably isn’t wrong about everything he’s ever said on this topic, just the central points under contention, and he has tons of company.

Noah Smith (Noahpinion) recently published a column in Bloomberg with the title “Health-Care Costs Are Still Eating the U.S. Economy.” This came to my attention because he was kind enough to link to my blog when he alluded to my arguments on health spending. Though there are obvious areas of agreement (e.g., that health spending has risen faster than income; that the so-called “cost curve” hasn’t been bent; that rising health spending puts a very real crimp on take-home paychecks amongst the working class), I strongly disagree with the central arguments he advanced and feel that he did not quite accurately characterize my views.

Noah wrote:

“In sum, health care is still eating the economy, and that’s still cause for alarm….Why is this happening? Some argue that the U.S. is just very rich, and that prosperous countries choose to spend more on health care, which drives up prices. They note, for example, that although U.S. health-care spending is unusually high as a percent of gross domestic product, it’s not th at high as a percent of individual consumption. But this isn’t very convincing, because consumption is a result of high health-care prices as well as an effect — high health care prices force Americans to use more of their income than people in other rich countries.”

He seems to misunderstand the argument and appears to be insufficiently aware of the evidence against his assertions. Since he is surely not alone in these thoughts, I am going to put some time into weaving together statistical evidence, supporting data, and thoughts I have strewn over a good number of blog posts, tweets, etc. over the years. My goal in this post is to parsimoniously explain the evidence at multiple levels, clear up misperceptions, and address probable objections for the benefit of those that have invested considerably less time into assessing the evidence for themselves.

(warning: this is going to be even longer than usual).

Income and causation

On material living conditions and its role in health spending

Practically all informed people recognize income is a particularly strong determinant of national health spending. Many of these same people also argue the US spends too much using Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as their preferred income measure.

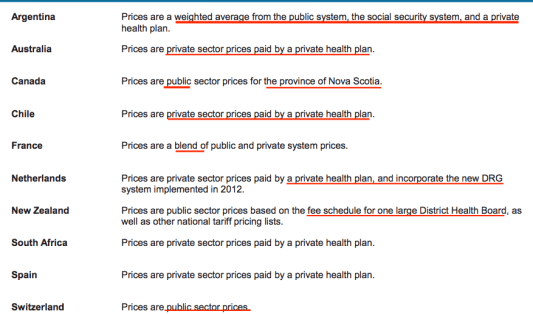

source

The problem is GDP is not even particularly a good proxy for the income of households (individuals). GDP is designed to measure how much value add is produced within domestic (territorial) boundaries. It usually does a fairly decent job of this, but it does not directly tell us about the household perspective, as in, the average level of real incomes or real consumption enjoyed residents of a country (a.k.a. “material living conditions“). Most importantly, it is an increasingly unreliable proxy for this concept.

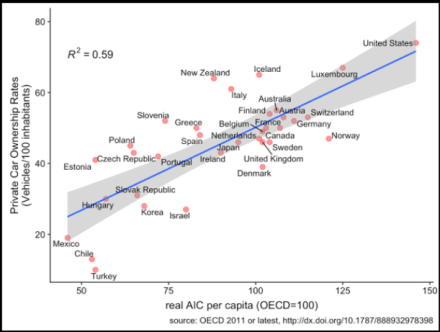

My position is national health spending is overwhelmingly determined by the average real incomes of countries’ residents in the long run (differences in propensity to consume may have a small role to play). The elasticity of national health spending with respect to reasonable measures of income or consumption is exceptionally high, averaging around 1.6 in OECD panel data, meaning that a 1% increase in income is expected to increase health spending 1.6% at a national level. Americans are exceptionally rich by these same measures, so it is hardly surprising we spend a tremendous amount on health care — far more than would be implied by simple regressions with GDP and far more than most people appreciate.

I first made this argument with Actual Individual Consumption (AIC) because it is a good indicator of material living standards and because that data was more readily available at the time. AIC is a comprehensive measure of household consumption that is adjusted for government transfers in-kind (e.g., health, education, etc.). Unlike earlier measures of household consumption (e.g., household final consumption) found in National Accounts, it does not systematically under-estimate the material welfare of social democracies where in-kind transfers constitute a substantially larger fraction of comprehensive household consumption or disposable income.

I subsequently demonstrated this same point using (Gross|Net) Adjusted Household Disposable Income (AHDI). Net Adjusted Household Disposable Income is little more than AIC plus Net household savings.

Note: “Net” simply means savings have been calculated to reflect consumption of fixed capital — basically depreciation — whereas “gross” does not account for this.

Unsurprisingly, wherever the data are available, they tend to be exceptionally well correlated.

For example:

So it can hardly be surprising the results don’t much change vis-a-vis health spending or representations of material living conditions. Even when we don’t have AHDI available directly, we can be reasonably sure AIC is a good proxy for it and vice versa.

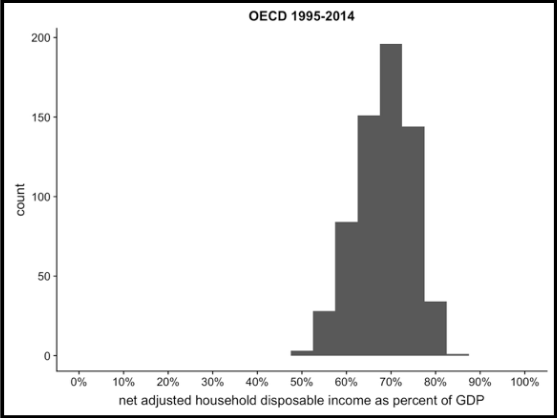

Like Gross Domestic Product (GDP), these economic aggregates are derived from National Accounts (SNA and its domestic counterpart). However, GDP and GNP are measures of production; they were designed for different purposes, and they actually measure different things. Although these measures are typically reasonably correlated, with AIC averaging around 70% of GDP, (Net) AHDI a smidge more, the relationship between production and welfare variables can vary quite dramatically within countries over time and between countries for systematic reasons. Significant differences can persist for quite a long time, and they are often explicable. Contrary to popular impression, it’s often not just transient noise.

Here are the primary reasons GDP does not relate directly to the household perspective:

- The movement of primary incomes across borders

- The incomes earned by non-resident workforces follow the workers home even if earned within the territory

- The incomes earned by foreign-owned corporations/quasi-corporations are counted in GDP even when distributed as dividends, rent, etc to residents of other countries.

- The movement of secondary incomes across borders

- Personal transfers, remittances, foreign aid, and international cooperation can raise or lower the standard of living in some countries in ways that are not reflected in GDP.

- The allocation of disposable income between domestic sectors

- In some countries, the corporate sectors account for a considerably larger share of GDP and/or national disposable income in the form of retained earnings (which don’t necessarily accrue to the ultimate benefit of residents).

- Differences in gross fixed capital formation requirements

- Some countries need to invest considerably more and face higher rates of depreciation just to maintain production levels.

- Higher rates of corporate investment, for example, might be better ceteris paribus, but countries with higher rates of investment aren’t necessarily better off.

- GDP itself may be systematically miscalculated due to corporate tax avoidance whereas the household perspective is relatively more immune to the incidental effect of this gaming.

- The prices faced by consumers are not the same as those faced by producers.

For these and several other reasons, the relationship between GDP and measures of material living conditions varies substantially between countries and within countries over time.

Histogram of AIC as a percent of GDP

Histogram of disposable income as a percent of GDP

Household material living conditions can evolve quite differently than GDP over many years.

And the cross-sectional relationships can vary over time (note: the connection has decayed notably in the OECD over the past few decades).

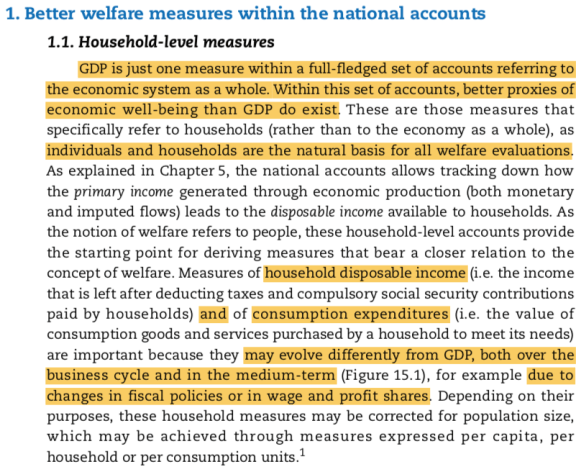

These measures enjoy substantial theoretical support.

AIC and AHDI are identical to those recommended by Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, and other notable economists in the “Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress” (a useful primer) and they have been part of System of National Accounts (SNA) for quite some time. These indicators have a strong theoretical basis, and they are widely preferred by experts over oft-cited production measures (e.g., GDP) when we want to compare how many resources households actually have at their disposal.

Here are some relevant quotes that speak to some of the issues:

Adam Smith – An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations:

“Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer. The maxim is so perfectly self-evident that it would be absurd to attempt to prove it.”

Simon Kuznets – 1934 Report to Congress:

“The valuable capacity of the human mind to simplify a complex situation in a compact characterization becomes dangerous when not controlled in terms of definitely stated criteria. With quantitative measurements especially, the definiteness of the result suggests, often misleadingly, a precision and simplicity in the outlines of the object measured.”

[snip]“The welfare of a nation can, therefore, scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income as defined above.”

1993 System of National Accounts:

“GDP is a measure of production…movements of GDP on their own cannot be expected to be good indicators of changes in total welfare unless all the other factors influencing welfare happen to remain constant, which history shows is never the case…Disposable income as measured in the System can be compared with the concept of income as it is generally understood in economics. From a theoretical point of view, income is often defined as the maximum amount that a household, or other unit, can consume without reducing its real net worth.”

2008 System of National Accounts:

“Per capita growth rates in real national income or in real actual consumption generally provide a better measure of the changes in the average “welfare” of a country’s population than the changes in GDP volumes. GDP is a measure of production within a country but the inflows or outflows of income from or to the rest of the world can have a significant effect on both the level and growth rates in real national income per capita. Similarly, the level and growth rates in GDP volumes can differ significantly from those in the final consumption of households because of the varying shares across countries of capital formation and net exports within GDP.”

[snip]“The adjusted disposable income of a household can be interpreted as measuring the maximum value of the final consumption goods or services that it can afford to consume in the current period without having to reduce its cash, dispose of other assets or increase its liabilities for the purpose. Its consumption possibilities are determined not only by the maximum amount it can afford to spend on consumption goods and services (its disposable income), but also by the value of the consumption goods and services it receives from government units or NPISHs as social transfers in kind.”

Report of the Commission on The Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress:

“In a world of globalization, there may be large differences between the income of a country’s citizens and measures of domestic production, but the former is clearly more relevant for measuring the well-being of citizens…the household sector is particularly relevant for our considerations, and for households the income perspective is much more appropriate than measures of production.”

The Report — [Recommendation 1: Look at income and consumption rather than production]

“GDP mainly measures market production…. However, it has often been treated as if it were a measure of economic well-being. Conflating the two can lead to misleading indications about how well-off people are…Material living standards are more closely associated with measures of net national income, real household income and consumption – production can expand while income decreases or vice versa when account is taken of depreciation, income flows into and out of a country, and differences between the prices of output and the prices of consumer products.”

The Report — [Recommendation 2: Emphasise the household perspective]

“While it is informative to track the performance of economies as a whole, trends in citizens’ material living standards are better followed through measures of household income and consumption. Indeed, the available national accounts data shows that in a number of OECD countries real household income has grown quite differently from real GDP per capita, and typically at a lower rate. The household perspective entails taking account of payments between sectors, such as taxes going to government, social benefits coming from government, and interest payments on household loans going to financial corporations. Properly defined, household income and consumption should also reflect in-kind services provided by government, such as subsidized health care and educational services. A major effort of statistical reconciliation will also be required to understand why certain measures such as household income can move differently depending on the underlying statistical source.

Understanding National Accounts, Second Edition [OECD publication]

In short, while GDP is not always a wholly unreasonable proxy in lieu of better alternatives, we reliably know it is not actually directly measuring the variable of interest (the resources available to residents), and we see this proxy (GDP) can be wildly misleading.

In summary, if we want to compare the resources available to residents of countries to spend, we should strongly prefer measures of material living conditions (direct measures) over indirect economy-wide production measures like GDP wherever the data allows.

This is about prediction and causality.

Contra Noah, my argument is not merely that US health spending “is not that high as a percent of individual consumption” whereby presumably changing the denominator from GDP (territory-wide production) to AIC (comprehensive household consumption) makes US health care look less unreasonable. It goes far beyond the United States or which denominator we reference. My position is the average level of real resources available to residents of a country is the ur-cause of the vast majority of health spending everywhere and that AIC and AHDI are plainly superior measures of this, ergo these indicators are vastly superior means to evaluate the efficacy of cost containment regimes everywhere.

As a proxy for the actual causal variable GDP is (increasingly) subject to various types of error. These errors both attenuate the apparent relationship between income and health expenditures in general and, specifically in the case of the United States, undoubtedly lead to dramatically downwardly biased predictions. We can do better.

Note: Economy-wide production, as measured by GDP, is clearly very important in the long run, but countries differ in their endowments, and there is not a simple linear relationship between measured GDP at any point in time and current income, or even the permanent income, countries’ residents — the r-squared is clearly much less than one. This is not an argument against the importance of production or even of the utility of GDP as a measurement for any and all purposes, but mostly an argument against naive application of it. We have better tools to understand how and why households behave as they do. The “rubber meets the road” at the household level in health consumption, even if mediated mainly by public and private institutions in the short run, as in most other forms of consumption.

AIC and AHDI are theoretically and empirically much more robust indicators of the resources available to residents of a country to spend or save. GDP only significantly determines health spending to the extent it determines material living conditions and the relationship between these indicators varies in the spatial and temporal dimensions.

This fits essentially no high-income countries on the regression line–indeed, they increasingly diverge! If one accepts GDP is reasonably well measured amongst high-GDP countries, and that “income” (GDP) is a strong determinant of health spending, this really ought to raise eyebrows. Clearly, something is rotten in the state of Denmark.

I say the meager health spending of most of these presumably high-income countries is remarkably consistent with their sub-par material living standards conditional on GDP. It is surely no coincidence that virtually all of these same countries tracks with their comparatively modest material living conditions.

We can also see some evidence of this in OECD panel data.

Likewise, we find AIC mediates GDP in this same USA-free panel data.

The 3rd specification above does relatively little to improve model fit and is likely over-fitting to some degree (it’s picking up defects in the model), nonetheless, it suggests changes in GDP means little for health spending without corresponding changes in AIC.

Alternatively, if we subtract AIC from GDP [note: this leave us with a figure comprised of collective consumption, gross capital formation, and net exports as defined in GDP expenditure method] so that the two predictors used in the 3rd model sum up exactly to GDP (expenditure method):

Model 3 implies that a 1% increase in AIC yields a ~1.43% increase in health spending whereas a 1% increase in everything else GDP (i.e., GDP-AIC) yields only ~0.11% increase (an order of magnitude less).

Lest you imagine this is some sort of mechanical effect, a consequence of health spending being included in AIC, we see similar patterns when we crudely subtract health from AIC!

The comprehensive household consumption is the clear victor over GDP in this horse race. These patterns become even more pronounced the more these indicators diverge, as in broader international data (not just OECD) and in cross-sectional analyses of OECD data from more recent years. We also find very consistent patterns in the cross-sectional data (i.e., between countries by year) and time-series for the vast majority of nations (wherein elasticity for health spending on AIC is clustered well north of 1 and GDP around 0, likewise for r-squared coefficients, etc.).

Household disposable income mediates GDP and other domestic sectors at least as well.

When we try to predict health spending using adjusted disposable income or the distribution of GDP according to its institutional sector (+RoW), we find a very consistent pattern: the resources (disposable income) in household sector are vastly more important than everything else. The resource found in the household sector effectively mediate everything else in GDP.

For example, in OECD panel data using Gross Adjusted Housing Disposable Income we find the coefficients for the household sector are several orders of magnitude larger than that for all other sectors combined and separately (including, notably, government!).

Similarly, if we assess these relationships as time series for each country, it’s quite evident that elasticity with respect to the household sector is clustered well north of one whereas it’s grouped around zero with respect to other sectors (government and corporate sectors).

Likewise, even if we subtract health spending from the household sector (RE: the mechanical argument), we find the same pattern.

We can also plot these regression coefficients, along with confidence intervals, to compare the effect of disposable income in the household sector versus government (see earlier link to see the other sectors–not much different)

elasticity with respect to household disposable income less health spending

elasticity with respect to government disposable income

It abundantly clear that GDP that shows up as disposable income in the household sector is vastly more predictive than GDP allocated elsewhere (e.g., rest of the world and other institutional sectors within the country). Clearly, this cannot be explained as a US-only phenomenon or as a mechanical consequence of how we allocate healthcare to household consumption or disposable income.

These measures are also superior predictors of just about every socially relevant metric!

This is not just about health spending! AIC is also a substantially stronger predictor than GDP with respect to the vast majority of socially relevant outcomes and their covariates. AIC also tends to mediate GDP for the vast majority of the variables we would associate with “wealthy” countries, whether for good (usually) and for ill (e.g., obesity rates).

Note: Most of these the outcome variable assessed below are lagged by several years relative to our economic predictors (FY 2011), suggesting this is picking up something more than just short-lived benefits of consumption.

Health outcomes

For example, AIC is substantially better correlated with nearly all of IHME’s health access and quality metrics.

Unsurprisingly, we find AIC mediates GDP in multiple regression (OLS) for these same metrics.

Note: The flipped associations for some cancer rates is likely a consequence of higher rates of diagnosis and longer life expectancy in rich countries. It is consistent with AIC being a better predictor of real health care consumption (quantities) and overall health outcomes.

Social Progress Indicators

To give another example, we find AIC trumps GDP with just about every metric available via the Social Progress Index.

World Happiness (survey measures)

Prosperity Index

Legatum’s Prosperity Index, a measure of business and economic conditions

Eurostat Quality of Life

These patterns described above aren’t likely to just be a consequence of some exceeding poor or backward countries because we find much the same in Eurostat’s QoL measures (mostly high-income countries)

Survey-based estimates of disposable income

AIC also aligns better with survey-based estimates of disposable income like Luxembourg Income Study (LIS).

While these survey-estimates are, in my view, quite flawed (substantial missing income, missing taxes, etc.) and inferior to their National Accounts-based cousins, it’s nonetheless notable that AIC does a better job picking up the signal they do detect.

There is much, much more I could show along these lines (I probably already wasted too many inches of screen space!), but the pattern ought to be clear: measures of material living conditions are not always well correlated with production across the whole domestic economy for a variety of reasons. None of this means that production (GDP) isn’t ultimately important, but it does suggest the relationship between measured production within territorial boundaries and the welfare of residents of a country is not as straight-forward or as tightly linked as some like to imagine. When the relationship between these aggregate measures diverge notably, we should put much, much more (instrumental) weight on the likes of AIC and much less weight (~0) on the likes of GDP if we’re interested in these sorts of questions, e.g., people, their preferences, household budgets, and lifestyle.

The US is not much of a consumption outlier.

Contrary to what Noah and others seem to imply, the US does not exactly stand-out in its consumption (AIC) to GDP ratio or its disposable income (AHDI) to GDP ratios. Amongst the OECD dataset (relatively high-income, high-HDI countries), the US is reasonably close to trend — a smidge high, but not particularly so.

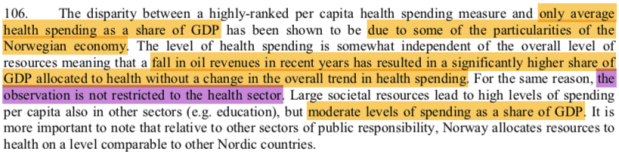

Luxembourg, Norway, Ireland, and Switzerland, on the other hand, lie much further away from the trend and far below it. This is very likely a consequence of idiosyncratic features of these countries, such as their economies’ exceptional economic reliance on cross-border workforces, corporate tax inversions, banking and financial services, and (temporary) oil-exports, which critically reduces the statistical relationship between material living conditions and measures of production (e.g., GDP).

Given the very high elasticity of health spending with respect to material living conditions (~1.6), these high-GDP outliers with large negative residuals will dramatically reduce the apparent “income” to health expenditure relationship if one imagines GDP is a good stand-in for individual income and does not selectively omit them from consideration. It is not as if these countries are unusually disciplined with respect to how they spend on health, most of the implied resources (GDP) over and above the EU28 mean just don’t show up anywhere in the household sector. As regards current health expenditures, their spending is far better understood concerning the resources available to residents (the Y-axis) than the amount of economic production happening within territorial boundaries for national accounting purposes (the X-axis).

We see much the same in the broader international picture (World Bank 2011 ICP).

(Or without trimming the particularly extreme outliers)

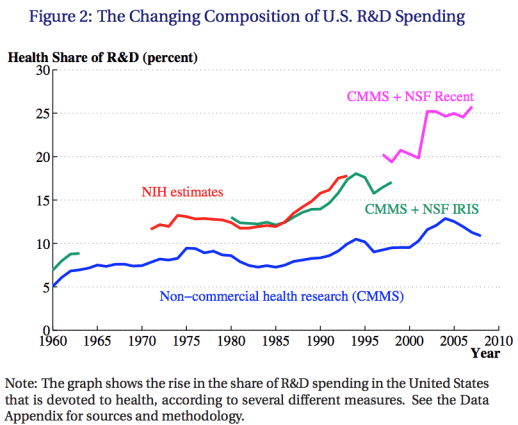

This is mostly about differences in the disposable income of households.

I have tended to use the consumption approach to material living standards because AIC is more widely available and probably slightly more reliably measured, but wherever the estimates are available or can be calculated from its constituent parts, it yields very consistent answers. Of course, this is not surprising given how closely household consumption and disposable income are correlated (which is likely attributable to the relatively small role differences in household savings rates play, both on a raw and “adjusted” basis).

For example, the patterns we find concerning net adjusted household disposable income as reported in OECD’s latest “Better Life Index” metrics are very similar.

Like we find with consumption (AIC), US net adjusted household disposable income is also apparently high conditional on GDP.

As I mentioned earlier, US consumption appears to be very much in line with its high disposable incomes.

Despite what many seem to believe, the US household savings rate actually compares quite favorably with much of Europe when disposable income is measured in a way that is invariant to whether government provides a relatively high proportion of goods and services in-kind (as opposed to them being purchased privately by households) — see health, education, etc.

Even if we don’t adjust it sensibly, US household savings rates are merely middling (and haven’t changed much over the past 20-30 years). If we use the more sensible “adjusted” measure of disposable income (AHDI), the US moves up in relative terms because the denominator in many social democracies is artificially low due to the relatively larger role of in-kind transfers in those countries [without adjusting for in-kind transfers the US lead in disposable income is far larger still].

Or, perhaps more revealing, comparing the trend in household financial net worth to comprehensive household consumption:

We can also compare a snapshot of household savings to GDP.

This is mostly about differences in the income actually enjoyed by households. The apparently high consumption of US households conditional on GDP is well explained by the high adjusted disposable incomes conditional on GDP.

Nor does this hinge on the exclusion of collective consumption.

I initially settled on indicators of material living conditions (the household perspective) because that is what economic theorists have settled on for welfare analysis. Many theorists argue collective consumption is (mostly) extraneous for welfare analysis; that it is an intermediate input to produce the welfare we measure at the household level. To quote the commision:

“Expenditures required to maintain consumption levels or the functioning of society could be viewed as a sort of intermediate input – there is no direct benefit, and in this sense they do not give rise to a final good or service. Nordhaus and Tobin, in their seminal 1973 paper, for example, identify as “defensive” those activities that “are evidently not directly sources of utility themselves but are regrettably necessary inputs to activities that may yield utility”. In particular, they adjust income downwards for expenditures that arise as a consequence of urbanization and a complex modern life. Many such “defensive expenditures” are incurred by government, while others are incurred by the private sector. By way of example, expenditure on prisons could be considered a government-incurred defensive expenditure and the costs of commuting to work a privately-incurred defensive expenditure.

[snip]First, focus on household consumption rather than total final consumption. For many purposes, the former is a more meaningful variable. And all of governments’ collective consumption expenditures (which would include things like prisons, military expenditure and the clean-up of oil spills) are automatically excluded from household final consumption.”

My own study mainly supports this: collective consumption is a much weaker predictor of health spending and the vast majority of other things we care about. That being said, the results I have found really do not hinge much on whether we try to predict with final consumption (AIC+collective consumption) or AIC alone.

In other words, US final consumption is still high conditional on GDP because US collective consumption is also actually quite high and final consumption tends to correlate quite well with AIC in practice.

The US is no slouch in collective consumption either.

So it can hardly be surprising the US residual is similarly modest concerning final consumption.

Nevertheless, I still prefer the household perspective (AIC, NAHDI, etc.) because of its theoretical strength and because it holds up better in repeated analyses I have performed.

For example:

Even if we crudely “adjust” AIC by removing health spending to address the “mechanical effect” objection, as in model 4, it still mediates collective consumption quite clearly.

The disagreement is mostly attributable to differences in the GDP share of the corporate sector and the flow of incomes across borders.

While the household perspective is surely the one we should be concerned with for our purposes, some people argue these results are primarily a consequence of some combination of differences in government savings/borrowing/investment or (collective) consumption behavior. One effective way to speak to this concern is to just combine the Net National Disposable Income (NNDI) of the household and government sectors together as if they were one entity, and compare it to the size of the corporate sector and Other (non-NNDI) as a share of GDP. NNDI is consumption + net savings, so this effectively addresses concerns over in differences in real savings too.

The combined sector for the US is still above average as a proportion of GDP, but more importantly, several countries in Europe are way below average. Their shortfall is explained both by proportionally larger corporate NNDI and “Other,” i.e., expenditures included in GDP not found in NNDI. “Other” includes things like consumption of fixed capital (depreciation) for all sectors, but it’s mostly large observable differences in net primary incomes (e.g., dividends, wages, rent, etc.) and, to a lesser degree, net secondary incomes (e.g., remittances) moving outside domestic boundaries. In some countries, such as the United States, the income going-in in modestly exceed those going out whereas, in others, such as Ireland and Luxembourg, they’re massively going out on balance (as a proportion of their small economies).

Another way to visualize this:

This gives a rough indication of how much is across borders (or depreciation) and how much is between domestic sectors (households+goverment vs. corporations).

Ireland and Luxembourg are just two particularly pronounced examples. However, similar patterns have been playing out elsewhere in less apparent but still cumulatively significant ways vis-a-vis the predictive powers of GDP and its association with the variable of interest. They are even more substantial when magnified by differences in GDP per capita and differences in PPPs (consumers vs. producers).

Differences in the relative size of the government sector, neither its savings nor its (collective) consumption, can’t explain away the US lead and, especially, the apparently large residual vis-a-vis GDP.

It’s also notable that US government net lending appears to be pretty close to its long-term average.

Nor have US household savings obviously departed from their long-term average.

Overall these results are consistent with the different impacts of globalization and the increasing importance of directly measuring material living standards instead of relying on proxies like GDP. [You might try reading this for a discussion of differences in the evolution of GDP and AHDI]

Nor is it likely US consumption has become detached from economic fundamentals.

As argued recently by Karen Dynan and Louise Sheiner in a Brookings paper on GDP and welfare, real GDP and real consumption have moved near identically in the US.

In other words, while the consumption share of GDP may have increased a few percentage points in nominal terms, it’s not “eating the US economy” in real terms. The difference between nominal and real movements must be resolved by differences in the evolution of price indices for producers versus consumers. This, in turn, is likely substantially explained by substantially under-estimated increases in nominal GDP (which probably relates to transfer price, profit shifting, etc.– which is reflected in differences in net exports, capital investment, etc.)

To quote Sheiner and Dynan:

“the rise of global supply chains and the legal latitude that companies have in declaring in which countries their economic activity takes place lend material downward bias to estimates of U.S. nominal GDP. In particular, ‘transfer pricing’ and other practices allow multinational enterprises (MNEs) operating in the United States to underprice the sale or lease of intangible assets—such as blueprints, software, or new drug formulas—to affiliates in low-tax jurisdictions so that more of their profits are booked in these countries.

The economic importance of such transactions has been documented in a variety of ways. For instance, in 2012, a Senate subcommittee questioned Microsoft about its agreements to shift some R&D costs and regional royalty rights to affiliates in Singapore and Ireland… In 2013, the subcommittee found that Apple used favorable transfer pricing agreements to shift billions of dollars of profits from the United States to Ireland… More generally, Hines (2005) and Lipsey (2006) show that U.S. MNEs register more profits in tax havens than can plausibly be accounted for by economic activity. [researchers] find that U.S. companies that have a cost sharing agreement with a foreign entity appear less productive than similar companies without such an agreement, and foreign companies that have a cost sharing agreement with a parent company in the U.S. appear more productive than similar foreign companies. A 2016 OECD brief described how such transactions drove a 26 percent increase in measured GDP in Ireland in 2015. And, Tørsløv, Wier, and Zucman (2018) estimated that nearly 40 percent of multinational profits are shifted to low-tax countries each year.

Under current methods, transfer pricing and profit shifting have led to an understatement of both nominal GDP and nominal gross domestic income (GDI). Consider the example of a smartphone whose software, blueprints, and branding are developed in the United States. If the phone is assembled in the United States, then the full value of the phone (priced at its market price) is included in GDP. If the phone is assembled abroad, then so long as the contract between the company doing the assembly (e.g. Foxconn) is an arm’s length transaction, GDP will still be correctly measured, as it will include the value of the phone less the amount paid to the foreign assembler. However, if a foreign-affiliate of the U.S. company is introduced in the transaction, GDP could end up understated. Here’s one way this could happen: the U.S. company leases the rights to the intangible capital—the software, blueprints, and branding—to an affiliate in a low-tax country (say, Ireland) and it prices that lease at a value that is much less than its market value. Then the Irish affiliate contracts with Foxconn to do the assembly. Phones are then exported from Ireland to the United States and from Ireland to the rest of the world. In this case, only the value of the lease from the U.S. company to the Irish company will be included in U.S. GDP, and if this lease is priced at an artificially low level, U.S. GDP will be too low as well.

Under current methods, estimates of imports associated with sales of the phone in the United States will be too high because the economic activity associated with the leased assets is unlikely to be attributed to this country. In particular, imports will be too high (because they will overstate the Irish content of the phone imported from Ireland), and exports will be too low (because they will understate the U.S. content of phones exported from Ireland to the rest of the world). The same bias would occur in GDI because of the understatement of the company’s U.S. earnings. Note that this transaction works because there is intangible capital that is hard to value and hard to pin to a location, and because the Irish company is an affiliate of the U.S. company, so that it does not matter to shareholders whether the Irish affiliate or the U.S. headquarters books the profits.

This problem is of increasing concern both because of the evidence discussed above regarding the importance of profit-shifting in today’s economy and, more generally, because of the growth in MNE activity in recent decades. MNEs are now a large part of the global economy… they accounted for $4.7 trillion of global value-added in 2017, an amount that was about the size of the fourth largest economy in the world at the time. The statistical community recognizes the issue, and the international statistical guidelines most recently adopted by the United Nations Statistical Commission (System of National Accounts 2008) called for estimates of the production activity of MNEs to reflect the economic ownership of intangible assets rather than the legal ownership.

Nevertheless, the near identical movement of real GDP and real consumption in the US does not mean we can necessarily expect the same in other countries’ time-series or that there is any closer of a correspondence between real GDP and real consumption (or household disposable income) in cross-sectional analysis than I have already shown at length. Quite the opposite, given the increasing challenges of accurately measuring GDP as a result of globalization, measuring consumption (or consumption possibilities for AHDI) directly becomes relatively more important for tracking the evolution of material living conditions between countries.

US health spending did not diverge from other developed countries until material living standards diverged from GDP internationally.

US health spending was thoroughly unremarkable for most of the seventies (and even later).

Despite the fact that one could tell the same story about the alleged importance of market failures in health care, excess health inflation, high physician wages, and so on and so forth before, the United States was not the highest spending and it was very close to the GDP-indicated trend up until around the late-70s to early 80s. If these presumably distinguishing factors didn’t cause relatively high expense before, why should we believe they explain high spending now? What changed?

I submit it’s no coincidence that US material living standards, while always high by OECD standards, did not start to diverge from other high GDP countries until around this same time period.

This difference, however, owes less to the change in US behavior than the much more substantial change amongst a handful of small high GDP countries, the combined effect of which broke the strong relationship between AIC and GDP that had existed previously within the OECD.

Even as late as 1980 the link was strong and the US was clearly close to trend, but in the eighties, nineties, and aughts the position that GDP maps consistently to individual income across countries or across time became increasingly untenable.

So it shouldn’t be surprising health spending followed a somewhat similar trend, albeit magnified given the high income elasticity of health expenditures.

The long-term trend for the US is pretty similar to what my crude model would predict when fitted without the USA in the training data, both regarding its initial position and the split from the rest.

It’s even closer when fitted with the United States, of course. Given the observed non-linear relationship, the magnitude of the US lead in AIC, the plausibility of the model, lagging/variable rates of response (not directly modeled), and so on I don’t think this is entirely unreasonable as a means to provide some context.

We see similar shifts play out in the consumption share of GDP.

To be clear, the PPP-adjusted panel data is very consistent with the argument that real consumption did not grow appreciably faster than real GDP in the United States. The difference is mostly found in other OECD countries where real consumption (and real household disposable incomes) failed to track with real GDP growth. This was likely substantially due to globalization, such as, increased cross-border workforces and tax avoidance behaviors of corporations (particularly predominantly US-owned corporations), which probably had an outsized inflationary effect on the GDP a handful of small countries (e.g., Ireland) while modestly deflating US nominal GDP.

US consumption patterns are highly consistent with its indicated material living conditions.

When Noah et al. blithely dismiss these arguments with assertions like “this isn’t very convincing, consumption is a result of high health-care prices as well as an effect,” I wonder if they’re paying attention. Never mind (1) that US health spending is also explained by high adjusted household disposable income or (2) the residual with respect to household disposable income is modest or (3) US leads in health-spending-adjusted-AIC and there is a significant positive residual in relation to GDP and so on and so forth, we can also see to degree to which this claim is plausible based on how consistent US consumption patterns are with its indicated material living conditions (AIC or AHDI).

If measured AIC and the like are inflated in a way that Noah suggests, I would expect the US to clearly stand apart out from the rest because presumably, health is pushing up consumption to a degree markedly different than other countries. That is, I would expect that health spending would be unusually high conditional on measured AIC and other categories, especially those with high elasticities, would be unusually low for a country with such high indicated material living conditions. We find no such evidence.

For example, if we run Principal Components Analysis on indices of the volume of expenditures per capita across all available expenditure categories and use the first component score, which explains the majority of the systematic variance, we find this score is very well correlated with AIC and that the US is very much on trend.

Note: we see this after adjusting for price levels for each category, as in the “real volume” measures above, and we find this when these categories are instead adjusted with broader PPPs like AIC or GDP

This same factor is comparatively poorly correlated with GDP (which, unsurprisingly, is entirely mediated by AIC)

Even when we progressively pare down the principal components analysis of these consumption categories in real per capita terms (as in, quantities per capita) we find tremendous alignment with the real AIC per capita indicated by OECD and others. For example, if we run PCA on real expenditures per capita excluding health, education, and transportation, things which people presumably believe the US is uniquely distorted in, we still find it’s well correlated with AIC and the USA is very close to trend.

And, again, we find GDP is comparatively weakly correlated with the extracted component.

Given the substantially different loadings/elasticities found in these analyses, we really shouldn’t expect to see this if our consumption was distorted as Noah implies, i.e., our real consumption in non-health categories should be notably consistent with a more impoverished country than indicated.

On the other hand, if you don’t trust dimension reduction techniques like PCA, you can painstakingly analyze the data category-by-category. You can still see that the US compares favorably on all categories reasonably well correlated or with reasonably high elasticity with respect to wealth, that it’s on the AIC trend and usually above the GDP trend. It’s not the negative outlier it ought to be if Noah’s supposition were correct.

As with these dimensionally reduced results, as with health spending, AIC is consistently substantially better correlated with these indicators of consumption and mediates GDP with respect to virtually every consumption variable with prosperity [with the apparent exception of alcohol and tobacco in OECD data — which is almost certainly due to non-resident shoppers in Luxembourg!]. We find this in broad international data (World Bank ICP), and we see this amongst the narrower subset of mostly high-income countries located in the OECD databases (a pattern which is even more evident if we regress on the remaining components of GDP after subtracting AIC)

The US plainly consumes much more across the board. It does so in a way that is highly consistent with the measured AIC or adjusted household disposable income.

And it’s often well above what would be indicated by GDP.

Interestingly, across a large number of consumption categories, the elasticity of consumption varies and varies in a way that is rather consistent across time with some modest exceptions, e.g., the growth of IT/communications (in real terms). In other words, if we have a reasonable estimate of real AIC per capita, we can make pretty good predictions across these consumption categories (especially those with higher elasticities), both regarding their real per capita and terms of their share of consumption expenditures. Again, despite different loadings, transforms, etc. used in these analyses, we find the US allocations across categories tracks well with real AIC per capita over time (even when framed on an annual basis as in this animated GIF)

Substantial reverse causation is not likely.

Typically when one wants to argue A (health spending) primarily causes B (overall consumption), A must plausibly precede B. However, the arrow of causation moves overwhelmingly from increases in (measured) material living conditions to increases in health spending because changes in household disposable income are followed several years later by even larger changes in health expenditures.

As discussed by none other than Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), disposable personal income (DPI), the domestic counterpart to AHDI, is a particularly strong determinant of health expenditures (elasticity =~ 1.4) and health spending lags it by several years due to delays in institutional responses (payers, employers, providers, etc.).

As discussed at length earlier in the paper, real per capita DPI is a highly influential variable in our model of private PHC spending. While our estimates are based on time-series data for the United States alone and include spending only by private payers, the importance of this variable is consistent with a large body of literature examining the empirical relationship between national income and health spending. A number of studies based on time-series cross-country data for the [OECD] economies confirm the importance of the link between health spending and income. It has been repeatedly shown that variations in real per capita GDP (used as a proxy for income due to data availability) account for a substantial share of variation in health spending across countries and time.

In the econometric model of real per capita private personal health care spending, income has a lagged effect on health spending. To capture the timing of these lags, the income term in our model of PHC spending is incorporated as a polynomial-distributed lag estimated over 7 years (from 6 previous years through the current period). Our estimates imply that the effect of income on private health care spending growth rises to a peak at a lag of about 2 years. The specification of the model with all variables expressed as log-differences (growth rates) implies that coefficients on model variables can be interpreted as price and income elasticities, which are constant over time.

Though fluctuations in growth in aggregate income have some immediate effects on growth in private PHC spending, these initial impacts are usually fairly small. The current-period income elasticity in the NHE Econometric Model is only about 0.2... The estimated lagged effect of income for private PHC spending growth peaks at a lag of 2 years. The effective long-term income elasticity of private PHC spending (the sum of estimated coefficients over 7 years) is 1.4…..

The long lags that are built into this model reflect several important characteristics of markets for health services. In particular, since private insurers or public payers account for the large majority of health expenditures, this spending is largely insulated from contemporaneous changes in household income. Furthermore, consumers generally do not pay for most medical expenses directly at the point of purchase. For the most part, the decisions of insured patients are not immediately affected by changes in income except in those cases in which substantial parts of the expenditure are paid for out-of-pocket….

The other critical element captured by the lag in the impact of income growth on private PHC spending is the role of multiple intermediaries between consumers and medical providers….Consequently, substantial delays may be required to implement any response to changes in underlying consumer preferences, both to negotiate any changes to contracts and regulations, and to implement such changes in a way that would influence choices of medical treatment in practice. In addition, in response to any modifications in the design of their health plans, employees may take time to respond to changes in incentives under the conditions of insurance coverage by gradually changing their patterns of health care consumption over time. Further, doctors and other medical providers may also respond gradually to changes put in place by payers. In the long run, responses could include altering treatment protocols in response to the incentives inherent in methods of payment for care and in response to constraints on coverage imposed by insurers. Because of these interactions among intermediaries, consumers, and providers, it is reasonable to expect that the response of the system to changes in income growth will extend over a period of years.

Furthermore, CMS clearly doesn’t think GDP is all it’s cracked up to be. Indeed, they use the disposable income of households as the dominant exogenous predictor variable in their long-term forecasts, and they note that real GDP per capita is “used as a proxy for income due to data availability” in international comparisons.

I have likewise plotted the all personal health expenditures (public AND private) in relation to analogous measures of material living conditions without incorporating any lags directly into the smoothers to make the sequencing a little more obvious (over the past few decades, as the role of 3rd party payment, has increased, the lag in response has grown).

The robust link between these variables goes back even further in the data I have reviewed, but the lag is readily apparent over the past few decades due to the growing role of 3rd party payers, both public and private (i.e., less and less of the economic burden of health consumption is on the consumers of health care).

Prices and Inflation

The relative increase in health spending is poorly explained by the increasing price of healthcare.

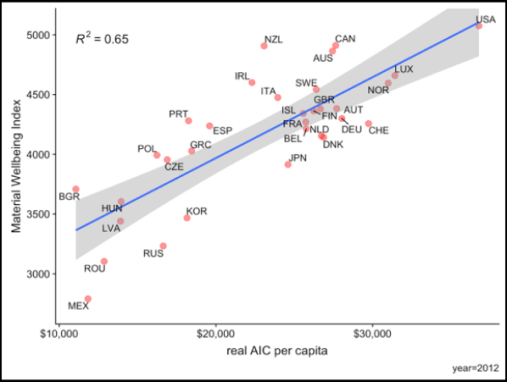

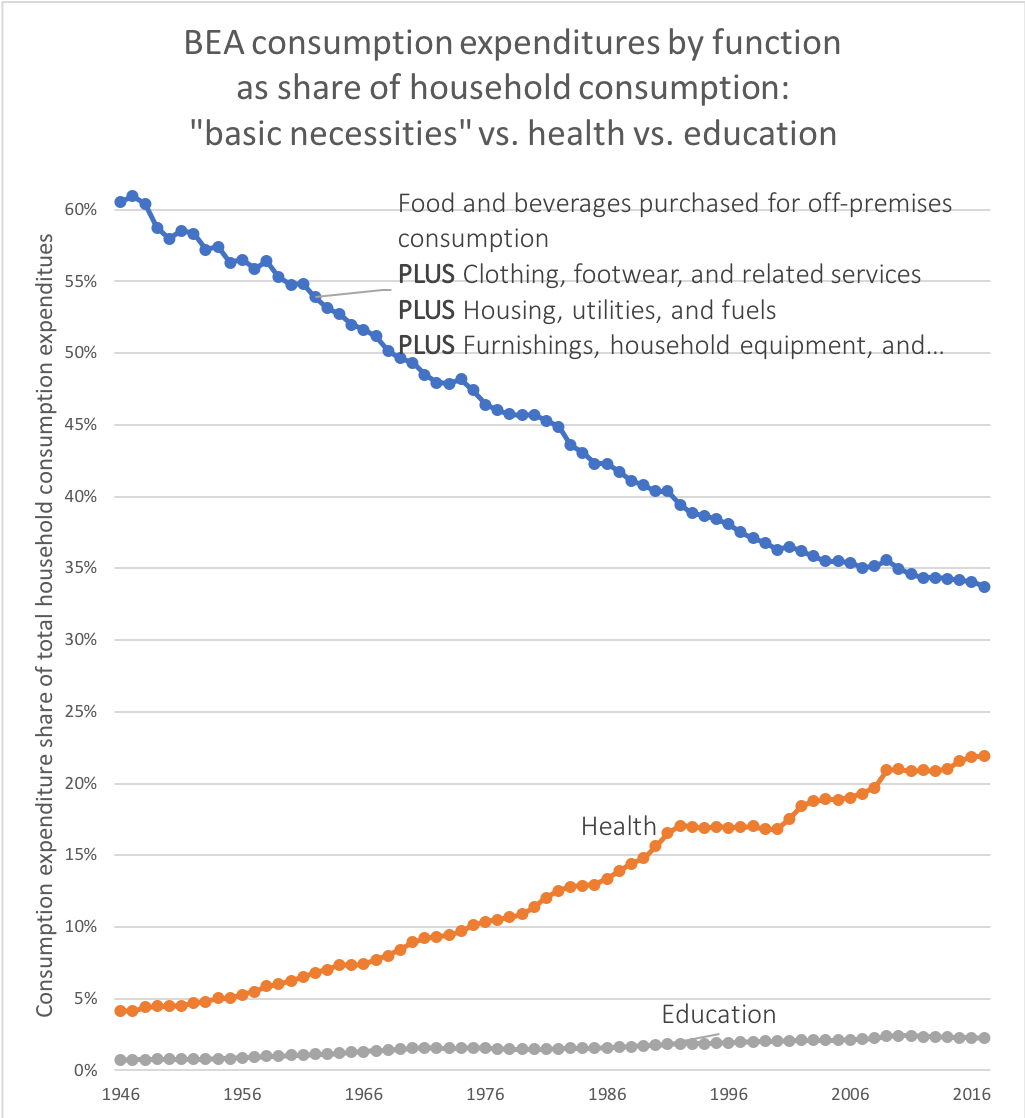

Contrary to Noah Smith’s ostensible argument and contrary to the explicit arguments of Josh Bivens of EPI, the rise in US health spending relative to incomes over the past several decades is poorly explained by any broad index of health inflation in the United States. All mainstream indices of designed to track the rate of inflation in the actual overall health prices, including the BEA index Bivens used, show that health price inflation can only explain a modest fraction of the observed increase in health spending relative to GDP, disposable income, or overall consumption over reasonably long time spans. Much to the contrary, the indices of health expenditure volume derived by BEA, CMS, and others imply the increase is mostly a consequence of real health consumption (as in “volume” or “quantity”) rising faster than real incomes. I suppose some may try to dispute the accuracy of these inflation measures, but this is clearly what is indicated by all of the major price indices!

While it is true the measured health inflation reported by these same indices typically exceeds the broader rate of inflation by a healthy amount, the long-run rate of measured health inflation has usually not even surpassed the long-run rate of nominal growth in income or consumption (certainly not by much for long).

data on FRED

The identity is price * quantity = value, ergo if the percentage change in price is less than the percentage change in the denominator with which we are evaluating value (e.g., nominal health spending / nominal GDP), the health share will decline unless the increase in quantity is substantially higher than zero (in this case appreciably greater than percentage change in GDP per capita).

If the health share of GDP (or PCE, DPI, etc.) actually increased, which it most certainly did, then it must be true that the quantity (volume) of health consumed increased faster than GDP increased. One just cannot reference an index of this sort to claim the increases have been driven primarily by price inflation. Adjusting for excess medical inflation (health inflation over and above the broader rate of inflation) reduces the apparent rate of real health spending growth somewhat, but clearly, the dominant factor according to these estimates is volume (quantity).

For example, between 2000 and 2016, a period in which nominal health spending more than doubled, nominal GDP and nominal disposable personal income grew significantly faster than the rate of measured inflation across broad indices of health prices and most of the sub-components (except for prescription drugs and hospital services with respect to GDP).

We find much the same in CMS’s price indices [Personal Health Care (PHC) being the price index of overall healthcare costs]

There is broad agreement on these points amongst CMS, BEA, and related government/statistical agencies with regard price indices designed to track the overall rate of inflation in the health care sector; all of them imply the (broad) inflation-adjusted increase in health expenditures (as in, deflated by CPI, PCE, etc.) over the past several decades is overwhelmingly a consequence of the quantity (volume) of health consumption rising faster than real incomes because these price indices simply have not substantially exceeded the rate of nominal income growth.

The results in earlier decades might be a bit more debatable because our price measurements likely weren’t as good. Nevertheless, even there the consensus view amongst experts that have actually researched this is that “excess” or “relative” health inflation (i.e., health inflation over and above the rate of general inflation) explains at most a modest fraction of the observed growth in health spending.

source

The majority of health inflation is not even reasonably attributable to “market failure.”

The health sector is a predominantly a domestic service sector. It is a labor-intensive industry that does not enjoy substantial productivity gains that result from technological improvements (e.g., automation) and, unlike most goods, the services cannot be readily traded with other (lower-wage) countries. As implied by Baumol’s cost disease, the productivity gains found in other areas of the economy tend to spillover as real wage growth throughout the economy, including the healthcare sector, and this wage growth will tend to be reflected as excess price inflation in the healthcare sector. The existence of cost disease is about as close to a consensus view as can be found amongst economists.

source

Health prices have only increased modestly faster than the overall service price index.

This is also much slower than the rate of inflation in education, not just higher ed, but also pre-K, primary, and secondary education. We also find inflation significantly over and above the average price index for most others services. One might be tempted to dismiss inflation in health and education as somehow unique, arguably a consequence of government intervention or market failure, but why else would we find this in so many other areas? So long as wages in these services reflect real income growth and their productivity does not increase as rapidly as the broader economy, I don’t see how we can reasonably expect much different than what we observe.

These are even less likely to be primarily attributable to unique features of health care in the United States because the evidence we see in other countries is broadly consistent with this.

For example, the pattern we see cross-sectionally is what Baumol’s effect implies: the relative prices of goods in high-income countries are much less than what we observe in low-income countries, vice versa for services. These patterns are even more obvious and more consistent with respect to AIC (as has been noted by OECD researchers), but I’ll display it with respect to GDP for doubters.

What this tells us is that services in general, not just healthcare, cost substantially more on average in high-income countries. Residents of these countries typically earn higher real incomes than residents of lower income countries and productivity gains are not enough to offset them.

Likewise, the relative price of healthcare is substantially higher amongst richer countries in OECD/Eurostat every year.

Put differently, as compared to the EU28 mean the real price of a comparable basket of medical goods and services varies substantially and is quite well explained by national wealth (albeit still not enough to explain more than a small part of the relationship between income and health spending).

We can also clearly see this as a trend in relative prices (health inflation over and above the rate of general inflation) amongst several European countries.

source

Likewise, the Harmonised Indices of Consumer Prices (HICP) published by OECD suggests health inflation faced directly by individuals has substantially exceeded that of overall inflation (“All Items”) in most developed countries and in the EU28 as a whole.

The modest excess healthcare inflation found in the United States is in no way unique. It is located in most other service sectors (those which are actually particularly reliant on domestic labor), and comparable results are found in the health sectors of other developed countries.

The best evidence indicates US health prices are consistent with its income level.

According to the price indices and derived volume estimates in several years worth of OECD’s PPP benchmarks, along with several closely related studies, both overall health prices and prices for the hospital services (surgical procedures) are not unusually high for a country of its income level. In other words, US health spending is overwhelmingly explained by volume (quantity).

For example, according to this 2017 OECD publication, the index of real volume per capita when adjusted by health PPP (prices) was 210.

This implies the US consumed 110% more health care than the average OECD country when adjusted for health prices whereas we consume 140% more at GDP prices. This, of course, reduces the imputed volume of health care consumed, as it tends to do in higher-income countries, but not unusually so.

The results I found in the published data for 2014 reveal much the same pattern.

Their published tables and plots for prices, both PPPs and price level indices, are entirely consistent with this, but they require some extra work to allow for ready comparison. For example, they show the price level index (PLI) for US healthcare was 114 in 2014 (just 14% above the OECD average), and PLI for hospital services was 130 (30% above the OECD average).

Both of these are far the highest and would be much less than what one might naively predict based on incomes (see here for a clearer illustration for 2011).

PLIs are a little hard to interpret because it is the ratio of the PPP to the market exchange rate and, particularly in the case of the US, can be a bit misleading. My preferred method to illustrate pricing is to just divide the PPP (e.g., health) by the broader PPP to give a reasonable sense of domestic opportunity cost. As in, how much more of a basket of consumption/expenditure (AIC or GDP) must one give up in given country to buy an equal quantity of health services as compared to the OECD average.

This approach yields practical, readily interpretable results comparable to how people usually try to compare the prices of individual goods and services.

So, for example, we compare the price of overall health care to our index of material living conditions– we can see that the real cost of healthcare does appear to rise with national income levels (consistent with cost disease theory)

Likewise, but for hospital services (surgical procedures)

I trust the data produced by these OECD researchers for recent health PPPs a lot more than others because (1) they obviously put a lot more care into design, (2) they disclose their methods, (3) they draw on a much more extensive array of countries than the slip-shod stuff most people cite on these issues, and (4) they work in conjunction with multiple national health agencies. Most importantly, their methods actually allow us to reasonably infer true price differences because it allows for reasonably “apples-to-apples” comparisons.

Although I much prefer the finished product found in the published PPP benchmark estimates to assess the likely role of prices, one can also see earlier results comparing quasi-prices for individual surgical procedures by many of the same researchers in published papers. I took the liberty of plotting all available prices some time ago, but here’s a truncated version (results are very similar–US is not notably above trend).

And read this…

To give an example of the planning they put into this, click the links for types of costs assessed, case types used for hospital services, sample criteria for a particular case type, data collection sample for compensation, and mapping of occupations and skills. It’s surely not perfect, no method is, but it’s clearly been carefully done over many years, and it surely stands a good chance of being able to pick up the alleged sources of high costs in the US.

After this substantial effort, these researchers clearly found that the volume of health consumption per capita correlated strongly with material living conditions (AIC) and that the US health spending was still very high, regardless of the method used to deflate health expenditures (input or output).

And that price levels of health tend to be well correlated with broader price levels (usually higher than AIC in high-income countries, lower in low-income countries).

Let’s compare this to the International Federation of Health Plans (IFHP) results, which Josh Bivens and just about everyone else has inexplicably relied upon over the past few years to argue US challenges with healthcare are fundamentally unique and primarily about prices.

Despite IFHP’s nominal disclosure, it’s nonetheless apparent they mix and match data for different sectors and different regions of countries without any rhyme or reason:

They also combine data from different institutional settings.

![]()

And make comparisons across different bundles and goods and services.

![]()

They even sometimes have acknowledged some of the issues raised by their so-called “methods.”

Most of these comparisons are also drawn across a tiny number of countries and across a small subset of payer than often don’t reflect the actual composition of spending in those same countries. Their efforts in no way, shape, or form allow us to make “apples-to-apples” comparisons of prices in different countries.

I would also think some critics would be reluctant to take the ad hoc results of small, otherwise little-known, private health insurance trade group, that seemingly started publishing these powerpoint documents around 2009, that otherwise has not been active in producing data for public consumption, and is not particularly transparent about how they go about this, but maybe that’s just me. A few grains of salt are in order. Regardless, potential conflicts and institutional reliability aside, this data smells.

Their prices don’t seem to be as well correlated with national income or with the price levels of other countries as determined by OECD in their Hospital Services PPP. This suggests measurement issues that extend far beyond US-specific measurement. Reliably measuring prices, particularly health prices, is hard even when it’s not a politically charged topic and I see no reason to take their half-hearted attempts seriously.

Utilization and Intensity

Metrics that do not meaningfully predict spending elsewhere should not be used to argue US expenditures are not driven by volume.

Many people insist on using metrics that are poorly correlated with health expenditures to argue the challenges the United States faces in health finance have nothing to do with excess volume. As many others have done before, Bivens cites what he calls “broad measures” of health activity, namely physician visits and hospital stays (discharges), to argue “Americans use less health care.”

While these measures may seem to make sense superficially and might have made some sense circa 1930, when physicians provided most of what little the sector could offer patients, they don’t make much sense as a way to assess differences between countries or changes over time in recent years.

source

source

Even more on point, they clearly do not correlate with spending cross-sectionally within the OECD.

Doctors consultations are not correlated with health spending.

Nor in-patient discharges!

Nor curative care discharges!

Nor curative care bed-days

It’s not like we don’t have plentiful evidence that health spending is rising more rapidly than income in other countries and that this is mostly a result of rising real consumption–both within and between countries. However, the same indicators proffered by others fail to meaningfully explain the rise in health spending elsewhere!

You may not like it, but this is what peak healthcare performance looks like.

If you accept the premise spending is rising rapidly in other countries and that this is mostly real (not prices), as the evidence strongly suggests, you ought to re-evaluate how you think about the drivers of health-care costs (especially volume.)

It’s the intensity, stupid.

There is an important, much neglected, omitted variable in most popular analyses of health spending. Much evidence suggests (1) real health consumption is rising much faster than incomes throughout the OECD and (2) measured utilization and its covariates (e.g., disease burden) have not changed very much. There is no necessary reason why these facts must be at odds with each other.

source

We see this same pattern inside and outside the United States. There is a huge, often omitted, third variable, a categorically different way to think about this: we do much more per health system encounter and/or per sick patient than we once did.

Let’s call this intensity.

Expenditure = Price * Volume

Volume = Utilization * Intensity

Expenditure = Price * Utilization * Intensity

Even if price and utilization actually remained wholly unchanged (they’re not quite), both volume and expenditures can rise rapidly and in-lock-step with percentage increases in intensity.

The overall growth in health care relative to income cannot be plausibly explained primarily as a consequence inflation over the past few decades because these changes are pretty well captured by differences in the types and quantities of these goods and services and poorly explained by price changes for the same goods and services.

For example, above and beyond the earlier discussed price index data and derived volumes, researchers found the substantial overall growth in health spending amongst the privately insured was approximately 100% explained by rising quantities.

These results are highly consistent with the price and volume indices constructed by government agencies (BEA, CMS, etc.) going back decades and compatible with virtually every other study of reasonable scope.

Some other people have argued it’s “price” and cited several studies to support their arguments, but the underlying studies are not methodologically equipped to support this claim (though some authors imply otherwise when talking to the press or in other public fora).

Here is a typical example:

“A recent study in JAMA by scholars from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle and the U.C.L.A. David Geffen School of Medicine also points to prices as a likely culprit. Their study spanned 1996 to 2013 and analyzed U.S. personal health spending by the size of the population; its age; and the amount of disease present in it.”

If you actually look at the study what they actually measured is what they call “price and intensity.”

This is little more than the average cost per health system encounter, as in, per visit, per bed-day, and per prescription filled. Changes in price were not actually assessed and no account was made for differences in treatment on a per encounter basis (new or changing composition in surgeries, drugs, devices, diagnostics, etc.). In other words, their data are very consistent with my arguments and with the indices reported by CMS and BEA, even though how they sometimes lead people to believe something very different.

Given the available evidence from other OECD countries (e.g., bed days, discharges, physician visits, etc.) it’s likely their (domestic) data if assessed with similarly granular “utilization” indicators, would show much the same. In other words, most would show at most very modest increases in “utilization” and thus most of the observed growth could be similarly lumped into “price and intensity” if it were reported similarly. Meanwhile, as in the US, we know the price indices don’t support this over reasonably long time spans (not in most developed countries at least), so that pretty much leaves us with “intensity” and there are a good number of indicators to support this view.

My arguments on the role of price, volume, and income are also consistent with the empirically-derived assumptions used by CMS’s Office of Actuary (OACT) in their 75-year medical expenditure models.

Put differently, the rise in health expenditures relative to income is primarily one of technological change, not excess medical inflation, and CMS OACT models it mostly as an enormous income effect.

In short, the government actuarial models, a reflection of mainstream thinking amongst subject matter experts, places little weight on prices, little weight on utilization, and a great deal of importance on technology (and its relationship to income) in the growth of health spending over the past forty years and going forward.

Incidentally, the dominant role of technology/intensity (broadly speaking) as a proximate cause of health spending helps partially explain the differences between the income-elasticities observed at a national (>1), regional ( > 0.5, < 1), and individual level (~0). Even if utilization and prices vary little with income at these levels of analysis, the intensity of medicine is primarily determined at higher levels of aggregation. For instance, if the standard of care is mostly determined by the average (mean) resources available in the larger community, the intensity with which health providers and hospitals diagnose and treat given symptoms/conditions isn’t likely to vary appreciably with the individual income of the patients (save for to the extent this indicates the mean of the broader community).

Given that the individual income elasticity for health expenditures is approximately zero in the United States and most other developed countries, the plot for average expenditure by income decile should look roughly like this within the OECD.

A very rich person in a poor country, for example, isn’t likely to get an MRI scan if he presents with a head injury at an emergency room in his own country. Even if he could afford the fees at US prices, there isn’t the critical mass of people that could afford, let alone demand, that on the margins. Conversely, a low-income person in a rich country may prefer to take a bit more risk under comparable circumstances in the United States and opt-out of such cutting-edge medicine if the choice was left up to him, finding such cutting-edge care to only be worth a fraction of what it costs society (probably similar patterns at the state/regional level with spillover effects and cross-subsidization from rich to poor states/regions )

The United States does more procedures, uses more diagnostics, and exhibits other characteristics that actually are associated with higher income, higher spending, and higher intensity.

Technology and that which is associated with it (additional staff, training, etc.) is the overwhelming proximate cause of rising health spending within and between countries, as in, more new procedures, diagnostics, pharmaceutical/biotech, medical devices, and so on and so forth. While the US may not consume more of those things that are mainly uncorrelated-to-even-modestly inversely associated with health expenditures in both the temporal (over-time) and spatial (between-country) dimensions, the bulk of the available objective measures indicates the United States does more of those things that actually are correlated with income and health spending in both dimensions.

Noah is just wrong on this bit:

“Looking at how often Americans use specific medical services such as knee replacements and C-sections, he finds that they generally tend to use fewer of these procedures than people in a number of other developed countries.”

(emphasis mine)

More importantly, the US is typically right about where we would expect it to be concerning those direct measures of volume which are well linked to higher health spending (especially when they are). Examples of these in published data include CT scans, MRI scans, coronary bypass, knee replacements, hip replacements, kidney transplants, and so on and so forth.

We also do less of those things (and covariates) that are inversely associated with income and health spending (especially when they are).

Of course, these sorts of indicators are just the tip of the iceberg. They are not nearly comprehensively enough to directly explain even half of the difference directly– not in the US or in other OECD countries–exhaustive indicators of this sort aren’t even available domestically (I wish!). By the time OECD, WHO, and company get around to tabulating and reporting such metrics across a reasonably large number of countries, the indicators often already a little dated, as in, higher-income, higher-spending locations have already started moving onto newer tech, procedures, etc. Nonetheless, where such data are available they are (on the whole) very consistent my arguments and the body of literature I’ve cited.

As discussed in yet another blog post, one can assess the available indicators somewhat more systematically, e.g., compare the loadings or correlation coefficients to the average values for the US as compared to other OECD countries. Here, too, we find observable characteristics in procedures, diagnostics, and the like offer a reasonable amount of explanatory power overall and we see the US generally on-trend.

It’s not a coincidence the US has a much larger health workforce than others — a major input into health care costs.

Nor is it a coincidence health sector’s share of employment (head counts, not wages) has grown markedly.

source

Indeed, if one looks at health spending from the point of view health expenditures per full-time equivalent (FTE) employed directly in the health services sector, it is likely there has been approximately no significant sustained increase over and above material living conditions.

In other words, this isn’t likely to be explained by health wages or profits rising substantially faster than real economic growth in the long run. Instead, this is primarily explained by rising real inputs [e.g., number of employees, their skill level (see nursing and technicians) and, to a much lesser degree, the costs of those inputs rising with average incomes without productivity improvements fast enough to offset them (mostly Baumol’s effect).